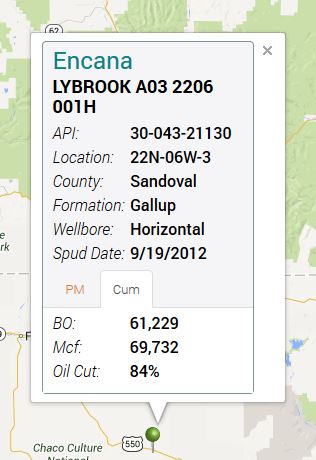

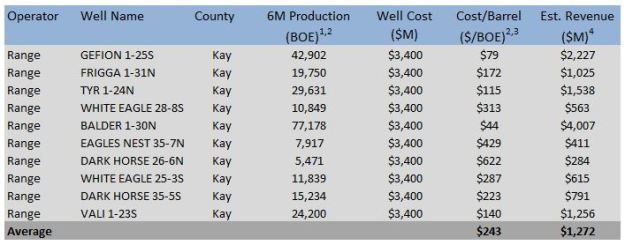

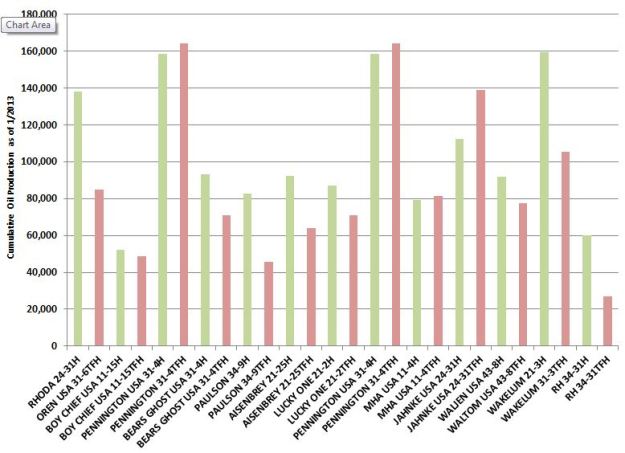

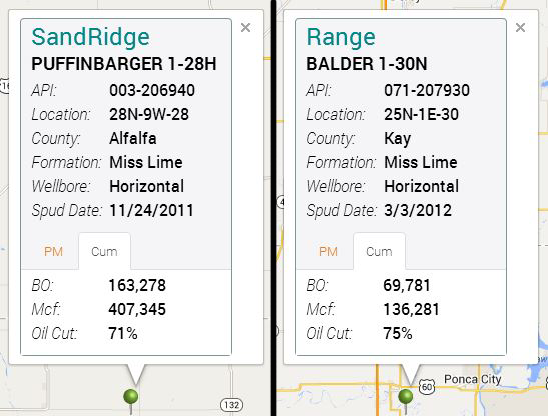

The Mississippian Lime has put companies and investors alike on a roller coaster ride during the last couple of years. When SandRidge Energy (SD) and Range Resources (RRC) started hitting big wells such as the Puffingbarger 1-28H and Balder 1-30N (see below), EUR and IRR projections ballooned to 600MBOE and more than 100%, respectively. Subsequent drilling has shown that these wells are more the exception than the rule, leading companies to slash their expectations considerably.

Big Wells in the Mississippian Lime

Source: The Well Map.

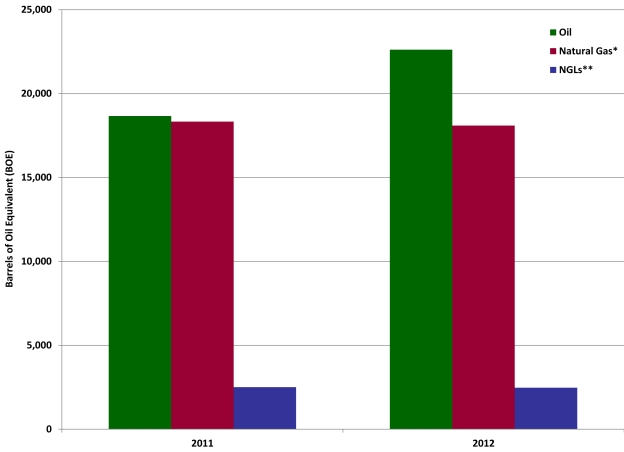

The Lime’s inconsistency has led some companies to leave the play and some to dial back expectations, but there’s reason to believe companies are finally starting to figure out its eccentricities. SandRidge saw production results improve approximately 20% from 2011 to 2012. These results coupled with a decrease in wells costs have increased the economics of the play.

SandRidge began drilling in the Lime in late 2010, meaning their oldest wells have produced for about three years. The company is currently estimating that its wells pay out in two years, so we took a look at their oldest producers to see if those estimations are accurate.

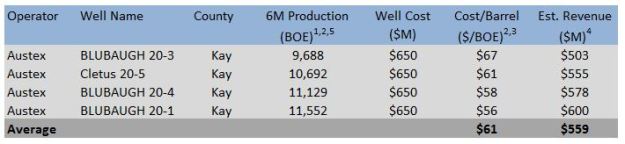

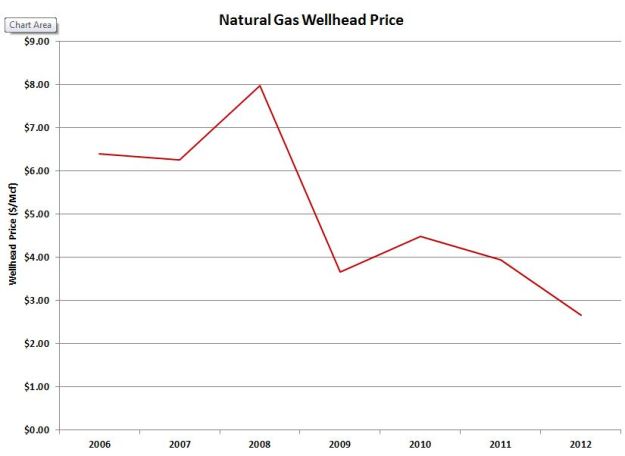

The average well the company turned to production prior to 2012 has produced 26 MBO (thousand barrels of oil), 197 MMcf (million cubic feet of natural gas) and 4 MBNGL (thuosand barrels of natural gas liquids). Assuming $88 oil, $4 natural gas, $40 natural gas liquids and an NRI of 80%, these wells have grossed $2.5 million in two years.

Revenue by Hydrocarbon

Source: The Energy Harbinger / Oklahoma Tax Commission.

This data tells us that SD’s early wells didn’t pay out in two years based on a $3.2 million well cost. While that’s an important data point, investors should be more concerned with the results from the next thousand SD wells than the first 100. So let’s compare these results to what we’re seeing from the company’s newer wells.

Average Production by Well During First Year (2011 to 2012)

Source: The Energy Harbinger / Oklahoma Tax Commission.

*Natural gas production converted to barrels based on 6:1 energy equivalency.

**Assumes 12% of natural gas stream is NGLs.

While natural gas production has remained flat, oil production by well increased approximately 20% from 2011 to 2012. This is important because oil is responsible for roughly 73% of a well’s revenue. If the 2012 wells continue to produce 20% higher than the 2011 wells, they’ll gross $3 million by their second year. SD is currently modeling sub $3 million well costs for the Lime wells, which means their newer wells are paying back in two years. A two year payback period is on par with most major oil plays in the United States.

At this point, we’re not sure why SandRidge’s newer wells are producing more oil. It could be that the company is able to focus on its better areas after it delineated it acreage or the new frac designs they’ve cited in their earnings transcripts are paying off. Either way, the production improvements make it a stock to watch for the future. To that end, Range is also tweaking its frac designs and has reported strong results in the few wells it has used to test the design.

If you track the Lime, you’ve probably heard of Petro River Oil (PTRC) who held its IPO earlier this year. The company has 85k net acres in the Mississippian and 32k net acres in a heavy oil play in Missouri. It recently attracted outside capital when Petrol Lakes (Chinese investment group) purchased $6.5 million in stock from Petro River. If you like micro-cap stories, these guys have an impressive management team which makes it a stock to watch.